Kevin Spacey

For the past five years Kevin Spacey's main focus has been his role as artistic director at the Old Vic Theatre in London. His productions have included The Philadelphia Story, Richard II and the recent Speed-The- Plow and he has also developed the Old Vic's education and community work. That said, Spacey's theatre work has not overshadowed an impressive movie career which includes starring roles in films as diverse as Se7en, American Beauty, and Midnight In The Garden Of Good And Evil. He has been nominated for numerous awards and has so far won two Academy Awards for his roles in The Usual Suspects and American Beauty.

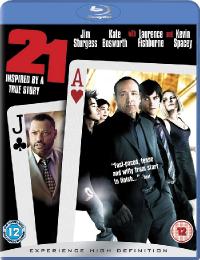

In 21 Spacey stars as Micky Rosa, the college professor who introduces his students to Las Vegas, the world of card-counting and high stakes gambling.

Q. Have you been surprised at maintaining a presence in American films while running London's Old Vic theatre?

A. "No, it was always my hope that I could maintain it. I suspected that when I started at the Old Vic that my focus would have to really shift.

"As much preparation as I did, as much research as I did about previous artistic directors and their roles, and as many conversations as I had with friends of mine who had been artistic directors, I really didn't know until I was in the middle of it just how much the job required, and what a really day-to-day job it was.

"I'm involved in every single aspect of the company, but as we've gone on and as we've grown it's been much easier for me to delegate because I now have an incredible staff.

"And I suppose that for me, when I look at this year, I made three movies last year. Even if the Old Vic didn't exist that's a lot of movies to do in one year. I think certainly for the first two years I really was focussing a lot, other than having shot Superman for six weeks, I was completely dedicated to the Vic.

"So the balancing act is trying to keep one foot in the film world but my first priority and my focus continues to be the Old Vic.

Q. Why do you need to do films, is it because you love them?

A. "Because I think to disappear entirely from films would be stupid. If it weren't for films I couldn't be doing what I'm doing at the Old Vic, that's for sure. But I also know if it weren't for theatre I wouldn't have had a film career. So I kind of feel like they complement each other.

"Although I do more producing in films than I do acting in films that's just really a measure of availability and time. There are movies that come along sometimes that I'm offered that I just can't do because I've already committed or we've already sold tickets to a production we're doing that I'm in. Once I make a decision to do a play I'm not going to change that, no matter what.

Q. Is 21 the kind of film you would have sought out, an old fashioned caper movie?

A. "Yeah, definitely. It's also got that Risky Business quality to it that I thought about when I first read that story, about 15 years ago, these rumours out of Boston from some friends that this thing was maybe going on.

"There's just something about what it's like when young people fall into making astronomical amounts of money in an unconventional way. And the potential of the greed and corruption, and the seduction that's thrown at them.

"It's about how they respond to it, and at the end of the day what decisions they're going to make and what kind of people they're going to be in the end. That's also the terrain that writer Ben Mezrich seems quite fascinated with; young men making a lot of money and what does it do to them.

Q. Would your former maths teachers consider your playing a maths professor a great leap of faith?

"Yes, I would say it would probably be one of the greater leaps of faith. But that's where acting comes in.

Q. How good are you at card counting?

"Look, I get it conceptually, it was explained to me and I nod my head and say it makes sense. And then the start doing the cards and it's like What? Stop! How many?'. And you're completely f***ed. I could no more count a single deck of cards than I could count six.

"Also if you meet the guys who were on the team, when we did what we like to call our research trips to Vegas - it's very important when you're a producer to take research trips - they're not allowed to play, but they could come with us and stand behind me while I played blackjack.

"Every time they wanted me to up my bet they'd just push against my chair. And I won every time. I wish they would just come around forever but they seem to have lives.

Q. Do films like Ocean's Eleven help with the financing of a movie like this?

A. "I don't know, we've had a kind of interesting journey on this movie because we found it five years ago. We sold it to MGM, they failed to tell us they were being sold so we went through four years of being parked and not knowing whether the film was ever going to get out of there.

"Finally Sony bought MGM, looked at the catalogue that were on the dock and pulled out two of them: James Bond and us. So we were very happy about that. But one of the things we were worried about was five years ago we thought we were ahead of the curve, because this movie was about Vegas.

"Then suddenly in the interim all these movies and all these TV shows and all these poker tournaments and all these reality shows, we were like 'f***, we're still f***ed'. One of the big issues creatively was how we make Vegas interesting again.

"One of the big reasons we wanted Russell Carpenter was that from a cinematography point of view to be able to make Boston, both its feel and its colours and the way its shot very different from Vegas and the life they take on there. The colours, the hues, the actual film we were using, was hugely important to us, because we were a little worried we might be behind the eight ball now.

"But I think that by doing the photography in the way that they have, by going into the cards, by going into the minds - I think it's very helpful for an audience to know how it works. I've always felt that movies about poker were very confusing to me because I can't figure out the hand. I can never figure it out.

"But 21 is such an easy game that even if you're a foreigner I think you're going to get what they're doing, you're going to get the game. You may not be able to count cards but you're going to get the game.

Q. Are you a fan of Las Vegas?

A. "For periods of time. I've had a lot of fun in Vegas when I've gone, you go for two or three days at a time, you're there with friends, having a party, getting drunk, going to all the places you're meant to go to and seeing the shows. That's all great. Being there for a month and some days is very different.

"I certainly didn't party while we were doing it, I didn't even gamble while we were there shooting, because of my responsibilities as a producer but also just the hours. You just can't do it. So I did a lot of other things when I had days off. It's just not a city for the day time.

Q. How did Vegas take to the production?

A. "You know, at first we wondered if we would be rejected by casinos, that they wouldn't want us. But then it turned out to be completely the opposite, they not only wanted us they welcomed us, they let us shoot in so many different casinos and places.

"I think it's because they secretly want everyone in America to see this movie and think they can come to Vegas and break the bank. So I do think there's an ulterior motive to their welcoming favours.

"But I've got to say Robert Earl in particular, who runs Planet Hollywood, couldn't have been better to us. It was our home base while we were there, it was where we all stayed, we shot quite a lot in Planet Hollywood. But all the other casinos where we shot were equally welcoming to us. I guess they look at it as an advertisement.

Q. Scenes of summary justice meted out to people beating the system might work in their favour too, even if they deny such things ever happen, by making potential winners think twice?

A. "Yes, and I hope you do.

Q. Are you much of a gambler yourself?

A. "I like the game 21, it's always been my favourite game. I don't play roulette, so it's just like a social thing, you go with friends and have a good time for a couple of days. But I've never been a gambler in the sense that I don't know when to walk away from the table.

Q. Do you find differences in attitudes to gambling in the US and UK/Europe?

A. "I don't think I've ever gambled here, only maybe once or twice at 50 and maybe once at the Ritz, but I haven't really gambled here a lot.

Q. But isn't it more open here?

A. "There's lot of places you can gamble in America, there's so many Indian reservations now where gambling is allowed, there's Atlantic City. There's certainly a lot of places in the south. It's not just Vegas, it's really all over the country.

"But there seem to be controversies about gambling here in Britain, I read all of that, so I don't know what will happen. But hey, if you like to gamble and you can handle it then do it. If you have a problem with it then, like anything else that's addictive, go get help.

Q. Are you a risk taker yourself?

A. "Yeah, I probably am. I think coming to London and starting a theatre company was probably a pretty big risk. But as I sit here in the middle of our fourth season, about to hit our millionth patron mark of audiences that have come in, it's encouraging for a fledgling theatre company.

Q. You weren't given the smoothest of rides when you started, were you?

A. "I didn't expect it. I think that's par for the course, if you go back and study the history of theatrical beginnings as I did when I started, you would easily have been as prepared as I was for the critical assessments.

"If you go back and look at the first three seasons of the Royal Shakespeare Company, they were a disaster according to the critics. Now we think of the RSC as the RSC, they can do no wrong. But when they started they were not welcomed. Sam Wanamaker was not welcomed with his idea of the Globe Theatre.

"Peter Hall had his critics, and he was called a disaster in his first three seasons at the National. Olivier had his critics. You just go down the line and you start to realise that that's the way things have been greeted.

"Now I kind of fully prepared myself for even worse, because I knew I was a film actor and I was an American and that seemed to be ripe for a sniper's target. And actually it was less personal than I thought it was going to be. And it ended when I hoped it would.

"By that I mean when they stopped judging the theatre company and it was about me. When it stopped being about my 'rein' and they started to judge the plays as the plays and judge them as plays.

"I always knew it would take us probably three or four seasons to establish ourselves, ad that's exactly what happened and that's exactly what I kept telling my staff. I said 'keep your heads high, we have a ten year vision, we'll get through this, it's been done before'.

"The truth is if I had have come riding down Waterloo Road on a white horse with Laurence Olivier on my shoulders, they wouldn't have liked me no matter what I did. So I did what I wanted to do.

"You have to also put in context why there was the passionate criticism [there was]. People have very, very strong, fervent memories of what the Old Vic theatre is to them. Both as critics, some of them have been doing it since the 50s, but also as young people they remember going to the theatre.

"So there is kind of an impression that the only thing belongs on the Old Vic's stage in some peoples' minds is Shakespeare, Ibsen, Shaw and Chekhov. Now I had to look at what I was facing which was a theatre that had ceased having an artistic director in 1976, that ceased being a company in 1976, and for 30 years was a booking house.

"There were two exceptions, when Jonathan Miller came and tried to start a company and when Peter Hall came and tried to start a company. They were not given subsidy and they both eventually abandoned those companies.

"My task was, how do we return the Old Vic as a destination theatre for audiences who'd not been coming for 30 years. Yeah, there'd occasionally be a hit play, but there was no audience development, there was no education, there was nothing like what we do with Old Vic New Voices.

"It didn't exist, it was a building - with a great history, but not a great recent history. So I had to face the question, it's a thousand seat theatre, it's not the Almeida, it's not the Donmar, it's not The Royal Court, it's a 1045 seat theatre. If you're playing under 70% you're dead in the water, because we have no subsidy.

"Our risks are our risks, and if we have a show that goes down it seriously damages us, particularly as we were just starting out. So what I had to look at was, alright, I could pretty much predict that people expected us to start with Shakespeare and Ibsen and Shaw and Chekhov.

"But I was fairly convinced that if I started there I would be playing to an already theatre going audience and that audience would be very now. And unless I put big stars in every show, that was not guaranteed you're going to be playing over 70%.

"The only way I felt to get a broader, more diverse and younger audience into that building and start to build an audience was to do work that I thought would be exciting, entertaining but maybe not what you'd expect to see on the Old Vic stage. But something that would bring more than the audience that already goes to Chekhov and Ibsen and Shakespeare.

"That's what we came under criticism for, what we programmed. And I maintain we were right to programme what we did because if we hadn't have gotten our audience in the first two seasons we wouldn't have lasted because there's no way I could convince anybody to keep giving us money if nobody's coming.

"I always said, although I guess some things you say just fall through the cracks, 'we'll get to the classics, we'll do the classic works, we'll absolutely do it'. Well now we've done The Entertainer, A Moon for the Misbegotten, we've got a Pygmalion coming in in the next couple of weeks.

"We've got Sam Mendes directing two classic plays over the next three seasons, a year in rep, so that's six classic productions that will be coming into the Vic. And at the same time we're doing new work like Pedro Almodovar's All About My Mother, Stephen Fry's Cinderella.

"We're trying to appeal in some ways to a slightly different audience with each production we do, and we're encouraged by the response of the British public. In the face of all of that criticism they never stopped coming, and I never stopped getting letters from the British public saying 'hang in there, hang in there'.

"And it was always my intention to hang in there, so I'm glad that it's going along alright.

Q. When were you first made aware of panto?

A. "Ian McKellen, because I went to Ian a couple of years before we started our first season and said 'you haven't been on the Old Vic stage since 1964 when you did Much Ado About Nothing in Olivier's company, I'd love you to come back to the Old Vic'.

"Of course I had visions of him wanting to do Shakespeare, and it was his suggestion that he wanted to do panto, and asked myself 'what's a panto?'. It was explained to me and then I did some research on it and I realised in fact - although we did come under criticism for doing a panto, because it wasn't in the tradition of the Old Vic - that was also untrue because the last time Aladdin was done at the Old Vic was 1860.

"So we actually were reaching back to its days not just as a music hall but also as a great theatre in history. So that production was the first panto I'd ever seen. It was shocking, but loads of fun.

Q. Anything else in British culture you'd taken to?

A. "I've definitely gotten into modern art in a way that I never really was before, I go to art galleries and see a lot of stuff. I've bought a few things. I'd sort of admired it before but I never really got into it, there's just such an incredible amount of places to go and galleries to see and openings.

"So I'm kind of flying in for a half hour and looking at some place and being introduced to a lot of interesting artists that are emerging. And some that have been around for a while, the Chapman Brothers and Paul Insect, Goldie's even become an artist and actually done some really interesting stuff. That's a scene that I'm getting more and more into.

"I've always been into the jazz scene here, on any given night I'm very happy to be cosily tucked into Ronnie Scott's. And of course theatre, and being able to go see all kinds of things. One of the great breaks I've given myself is that Speed-The-Plow is the first of the five plays I've done at the Vic where I made a decision that we wouldn't do Wednesday matinees.

"Simply because if you're just an actor in a play, eight performances a week, you can do it. But running the company at the same time, having a Wednesday matinee absolutely killed my week because it screws up Tuesday night, it screws up Wednesday, it screws up Wednesday night, it screws up Thursday morning.

"Doing two in a day is a lot. Especially if it's a play, as Speed is, that reaches a kind of epic, emotional life. So I'm very happy that I gave myself a break because it's given me another chance to go see things on Wednesday when I normally wouldn't be able to.

Q. How hands-on a producer are you?

A. "I am very involved until I step on the set. Once I'm there I'm there as an actor, if there's questions, or solutions that you have to come up with because there's a problem that's usually taken off set so that I can have that discussion off set. I just don't like to be in the kind of producer role when I'm acting.

"But I've been as hands on with this project from the second we found the Wired magazine article right through all of its script incarnations, and the casting process and the hiring of the major creative people. And right straight through into advertising and everything else.

"I am not a producer in name, I am a producer in fact, as I am with almost everything we do with Triggerstreet.

Q. Is it easy for you to surrender to your director then?

A. "I never let a director do that, what are you talking about?"

In 21 Spacey stars as Micky Rosa, the college professor who introduces his students to Las Vegas, the world of card-counting and high stakes gambling.

Q. Have you been surprised at maintaining a presence in American films while running London's Old Vic theatre?

A. "No, it was always my hope that I could maintain it. I suspected that when I started at the Old Vic that my focus would have to really shift.

"As much preparation as I did, as much research as I did about previous artistic directors and their roles, and as many conversations as I had with friends of mine who had been artistic directors, I really didn't know until I was in the middle of it just how much the job required, and what a really day-to-day job it was.

"I'm involved in every single aspect of the company, but as we've gone on and as we've grown it's been much easier for me to delegate because I now have an incredible staff.

"And I suppose that for me, when I look at this year, I made three movies last year. Even if the Old Vic didn't exist that's a lot of movies to do in one year. I think certainly for the first two years I really was focussing a lot, other than having shot Superman for six weeks, I was completely dedicated to the Vic.

"So the balancing act is trying to keep one foot in the film world but my first priority and my focus continues to be the Old Vic.

Q. Why do you need to do films, is it because you love them?

A. "Because I think to disappear entirely from films would be stupid. If it weren't for films I couldn't be doing what I'm doing at the Old Vic, that's for sure. But I also know if it weren't for theatre I wouldn't have had a film career. So I kind of feel like they complement each other.

"Although I do more producing in films than I do acting in films that's just really a measure of availability and time. There are movies that come along sometimes that I'm offered that I just can't do because I've already committed or we've already sold tickets to a production we're doing that I'm in. Once I make a decision to do a play I'm not going to change that, no matter what.

Q. Is 21 the kind of film you would have sought out, an old fashioned caper movie?

A. "Yeah, definitely. It's also got that Risky Business quality to it that I thought about when I first read that story, about 15 years ago, these rumours out of Boston from some friends that this thing was maybe going on.

"There's just something about what it's like when young people fall into making astronomical amounts of money in an unconventional way. And the potential of the greed and corruption, and the seduction that's thrown at them.

"It's about how they respond to it, and at the end of the day what decisions they're going to make and what kind of people they're going to be in the end. That's also the terrain that writer Ben Mezrich seems quite fascinated with; young men making a lot of money and what does it do to them.

Q. Would your former maths teachers consider your playing a maths professor a great leap of faith?

"Yes, I would say it would probably be one of the greater leaps of faith. But that's where acting comes in.

Q. How good are you at card counting?

"Look, I get it conceptually, it was explained to me and I nod my head and say it makes sense. And then the start doing the cards and it's like What? Stop! How many?'. And you're completely f***ed. I could no more count a single deck of cards than I could count six.

"Also if you meet the guys who were on the team, when we did what we like to call our research trips to Vegas - it's very important when you're a producer to take research trips - they're not allowed to play, but they could come with us and stand behind me while I played blackjack.

"Every time they wanted me to up my bet they'd just push against my chair. And I won every time. I wish they would just come around forever but they seem to have lives.

Q. Do films like Ocean's Eleven help with the financing of a movie like this?

A. "I don't know, we've had a kind of interesting journey on this movie because we found it five years ago. We sold it to MGM, they failed to tell us they were being sold so we went through four years of being parked and not knowing whether the film was ever going to get out of there.

"Finally Sony bought MGM, looked at the catalogue that were on the dock and pulled out two of them: James Bond and us. So we were very happy about that. But one of the things we were worried about was five years ago we thought we were ahead of the curve, because this movie was about Vegas.

"Then suddenly in the interim all these movies and all these TV shows and all these poker tournaments and all these reality shows, we were like 'f***, we're still f***ed'. One of the big issues creatively was how we make Vegas interesting again.

"One of the big reasons we wanted Russell Carpenter was that from a cinematography point of view to be able to make Boston, both its feel and its colours and the way its shot very different from Vegas and the life they take on there. The colours, the hues, the actual film we were using, was hugely important to us, because we were a little worried we might be behind the eight ball now.

"But I think that by doing the photography in the way that they have, by going into the cards, by going into the minds - I think it's very helpful for an audience to know how it works. I've always felt that movies about poker were very confusing to me because I can't figure out the hand. I can never figure it out.

"But 21 is such an easy game that even if you're a foreigner I think you're going to get what they're doing, you're going to get the game. You may not be able to count cards but you're going to get the game.

Q. Are you a fan of Las Vegas?

A. "For periods of time. I've had a lot of fun in Vegas when I've gone, you go for two or three days at a time, you're there with friends, having a party, getting drunk, going to all the places you're meant to go to and seeing the shows. That's all great. Being there for a month and some days is very different.

"I certainly didn't party while we were doing it, I didn't even gamble while we were there shooting, because of my responsibilities as a producer but also just the hours. You just can't do it. So I did a lot of other things when I had days off. It's just not a city for the day time.

Q. How did Vegas take to the production?

A. "You know, at first we wondered if we would be rejected by casinos, that they wouldn't want us. But then it turned out to be completely the opposite, they not only wanted us they welcomed us, they let us shoot in so many different casinos and places.

"I think it's because they secretly want everyone in America to see this movie and think they can come to Vegas and break the bank. So I do think there's an ulterior motive to their welcoming favours.

"But I've got to say Robert Earl in particular, who runs Planet Hollywood, couldn't have been better to us. It was our home base while we were there, it was where we all stayed, we shot quite a lot in Planet Hollywood. But all the other casinos where we shot were equally welcoming to us. I guess they look at it as an advertisement.

Q. Scenes of summary justice meted out to people beating the system might work in their favour too, even if they deny such things ever happen, by making potential winners think twice?

A. "Yes, and I hope you do.

Q. Are you much of a gambler yourself?

A. "I like the game 21, it's always been my favourite game. I don't play roulette, so it's just like a social thing, you go with friends and have a good time for a couple of days. But I've never been a gambler in the sense that I don't know when to walk away from the table.

Q. Do you find differences in attitudes to gambling in the US and UK/Europe?

A. "I don't think I've ever gambled here, only maybe once or twice at 50 and maybe once at the Ritz, but I haven't really gambled here a lot.

Q. But isn't it more open here?

A. "There's lot of places you can gamble in America, there's so many Indian reservations now where gambling is allowed, there's Atlantic City. There's certainly a lot of places in the south. It's not just Vegas, it's really all over the country.

"But there seem to be controversies about gambling here in Britain, I read all of that, so I don't know what will happen. But hey, if you like to gamble and you can handle it then do it. If you have a problem with it then, like anything else that's addictive, go get help.

Q. Are you a risk taker yourself?

A. "Yeah, I probably am. I think coming to London and starting a theatre company was probably a pretty big risk. But as I sit here in the middle of our fourth season, about to hit our millionth patron mark of audiences that have come in, it's encouraging for a fledgling theatre company.

Q. You weren't given the smoothest of rides when you started, were you?

A. "I didn't expect it. I think that's par for the course, if you go back and study the history of theatrical beginnings as I did when I started, you would easily have been as prepared as I was for the critical assessments.

"If you go back and look at the first three seasons of the Royal Shakespeare Company, they were a disaster according to the critics. Now we think of the RSC as the RSC, they can do no wrong. But when they started they were not welcomed. Sam Wanamaker was not welcomed with his idea of the Globe Theatre.

"Peter Hall had his critics, and he was called a disaster in his first three seasons at the National. Olivier had his critics. You just go down the line and you start to realise that that's the way things have been greeted.

"Now I kind of fully prepared myself for even worse, because I knew I was a film actor and I was an American and that seemed to be ripe for a sniper's target. And actually it was less personal than I thought it was going to be. And it ended when I hoped it would.

"By that I mean when they stopped judging the theatre company and it was about me. When it stopped being about my 'rein' and they started to judge the plays as the plays and judge them as plays.

"I always knew it would take us probably three or four seasons to establish ourselves, ad that's exactly what happened and that's exactly what I kept telling my staff. I said 'keep your heads high, we have a ten year vision, we'll get through this, it's been done before'.

"The truth is if I had have come riding down Waterloo Road on a white horse with Laurence Olivier on my shoulders, they wouldn't have liked me no matter what I did. So I did what I wanted to do.

"You have to also put in context why there was the passionate criticism [there was]. People have very, very strong, fervent memories of what the Old Vic theatre is to them. Both as critics, some of them have been doing it since the 50s, but also as young people they remember going to the theatre.

"So there is kind of an impression that the only thing belongs on the Old Vic's stage in some peoples' minds is Shakespeare, Ibsen, Shaw and Chekhov. Now I had to look at what I was facing which was a theatre that had ceased having an artistic director in 1976, that ceased being a company in 1976, and for 30 years was a booking house.

"There were two exceptions, when Jonathan Miller came and tried to start a company and when Peter Hall came and tried to start a company. They were not given subsidy and they both eventually abandoned those companies.

"My task was, how do we return the Old Vic as a destination theatre for audiences who'd not been coming for 30 years. Yeah, there'd occasionally be a hit play, but there was no audience development, there was no education, there was nothing like what we do with Old Vic New Voices.

"It didn't exist, it was a building - with a great history, but not a great recent history. So I had to face the question, it's a thousand seat theatre, it's not the Almeida, it's not the Donmar, it's not The Royal Court, it's a 1045 seat theatre. If you're playing under 70% you're dead in the water, because we have no subsidy.

"Our risks are our risks, and if we have a show that goes down it seriously damages us, particularly as we were just starting out. So what I had to look at was, alright, I could pretty much predict that people expected us to start with Shakespeare and Ibsen and Shaw and Chekhov.

"But I was fairly convinced that if I started there I would be playing to an already theatre going audience and that audience would be very now. And unless I put big stars in every show, that was not guaranteed you're going to be playing over 70%.

"The only way I felt to get a broader, more diverse and younger audience into that building and start to build an audience was to do work that I thought would be exciting, entertaining but maybe not what you'd expect to see on the Old Vic stage. But something that would bring more than the audience that already goes to Chekhov and Ibsen and Shakespeare.

"That's what we came under criticism for, what we programmed. And I maintain we were right to programme what we did because if we hadn't have gotten our audience in the first two seasons we wouldn't have lasted because there's no way I could convince anybody to keep giving us money if nobody's coming.

"I always said, although I guess some things you say just fall through the cracks, 'we'll get to the classics, we'll do the classic works, we'll absolutely do it'. Well now we've done The Entertainer, A Moon for the Misbegotten, we've got a Pygmalion coming in in the next couple of weeks.

"We've got Sam Mendes directing two classic plays over the next three seasons, a year in rep, so that's six classic productions that will be coming into the Vic. And at the same time we're doing new work like Pedro Almodovar's All About My Mother, Stephen Fry's Cinderella.

"We're trying to appeal in some ways to a slightly different audience with each production we do, and we're encouraged by the response of the British public. In the face of all of that criticism they never stopped coming, and I never stopped getting letters from the British public saying 'hang in there, hang in there'.

"And it was always my intention to hang in there, so I'm glad that it's going along alright.

Q. When were you first made aware of panto?

A. "Ian McKellen, because I went to Ian a couple of years before we started our first season and said 'you haven't been on the Old Vic stage since 1964 when you did Much Ado About Nothing in Olivier's company, I'd love you to come back to the Old Vic'.

"Of course I had visions of him wanting to do Shakespeare, and it was his suggestion that he wanted to do panto, and asked myself 'what's a panto?'. It was explained to me and then I did some research on it and I realised in fact - although we did come under criticism for doing a panto, because it wasn't in the tradition of the Old Vic - that was also untrue because the last time Aladdin was done at the Old Vic was 1860.

"So we actually were reaching back to its days not just as a music hall but also as a great theatre in history. So that production was the first panto I'd ever seen. It was shocking, but loads of fun.

Q. Anything else in British culture you'd taken to?

A. "I've definitely gotten into modern art in a way that I never really was before, I go to art galleries and see a lot of stuff. I've bought a few things. I'd sort of admired it before but I never really got into it, there's just such an incredible amount of places to go and galleries to see and openings.

"So I'm kind of flying in for a half hour and looking at some place and being introduced to a lot of interesting artists that are emerging. And some that have been around for a while, the Chapman Brothers and Paul Insect, Goldie's even become an artist and actually done some really interesting stuff. That's a scene that I'm getting more and more into.

"I've always been into the jazz scene here, on any given night I'm very happy to be cosily tucked into Ronnie Scott's. And of course theatre, and being able to go see all kinds of things. One of the great breaks I've given myself is that Speed-The-Plow is the first of the five plays I've done at the Vic where I made a decision that we wouldn't do Wednesday matinees.

"Simply because if you're just an actor in a play, eight performances a week, you can do it. But running the company at the same time, having a Wednesday matinee absolutely killed my week because it screws up Tuesday night, it screws up Wednesday, it screws up Wednesday night, it screws up Thursday morning.

"Doing two in a day is a lot. Especially if it's a play, as Speed is, that reaches a kind of epic, emotional life. So I'm very happy that I gave myself a break because it's given me another chance to go see things on Wednesday when I normally wouldn't be able to.

Q. How hands-on a producer are you?

A. "I am very involved until I step on the set. Once I'm there I'm there as an actor, if there's questions, or solutions that you have to come up with because there's a problem that's usually taken off set so that I can have that discussion off set. I just don't like to be in the kind of producer role when I'm acting.

"But I've been as hands on with this project from the second we found the Wired magazine article right through all of its script incarnations, and the casting process and the hiring of the major creative people. And right straight through into advertising and everything else.

"I am not a producer in name, I am a producer in fact, as I am with almost everything we do with Triggerstreet.

Q. Is it easy for you to surrender to your director then?

A. "I never let a director do that, what are you talking about?"

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!