Review for Earth (Zemlya)

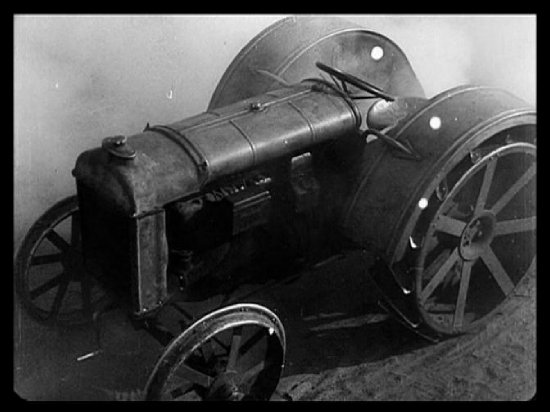

Old man Simon, who has worked as a farmer all his life, has died. His son Peter and grandson Basil argue about buying a tractor to help overcome their workload. The workforce are split between two factions - the old affluent farmers feel this will signal 'the end' while the poverty-stricken youth believe this new machine will allow them to prosper. Horses look on in dismay. When the machine arrives, it breaks down. The workers unite and urinate in the radiator. It starts up again. This beast of a machine ploughs through the harvest with uncanny ability, outside the realm of human endeavour…

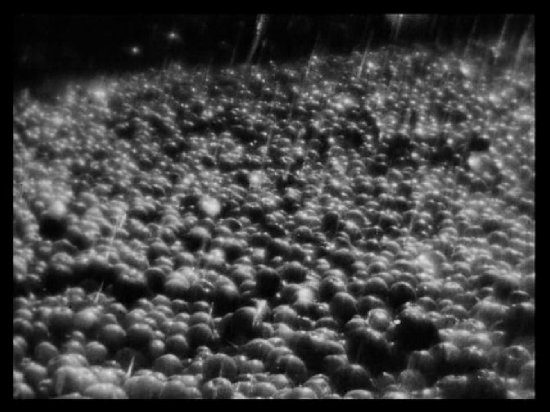

As Basil dances home, an assailant shoots him. His father Peter revolts against the village, trying to discover who killed his son. A priest tries to comfort Peter. He replies, 'there is no God' and asks the villagers if Basil can be 'buried in a new way. No priests and parsons singing of death'. The elders agree and let the workers 'sing the new songs of the new life'. The townsfolk flock to the funeral. The priest asks God to 'punish the sinners' while Basil's murderer runs through the harvest in anguish, admitting to his crime. The villagers sing songs of change, ignoring the killer's plea for reprisal. As the workers celebrate the birth of a new age, rain falls on their new harvest…

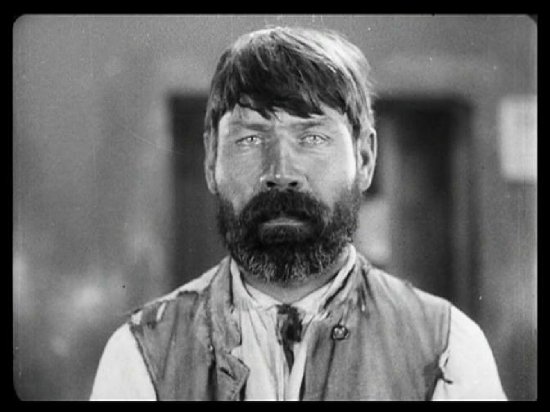

Why is it a weird and wonderful experience, watching an eighty-year-old film? It's because the visual language of cinema has morphed into a completely different beast since the advent of sound. So much so, that it is difficult to appreciate and understand the ocular assault of a 1930 'political' silent film like Alexander Dovzhenko's Earth (Zemlya). No matter how clever you think, you are. The true magnitude of Soviet symbolism will be lost on the majority of modern audiences who have grown up with the classical Hollywood style of storytelling. What is fascinating about Earth is experiencing these strange snapshots of a life different to our own. How we react to this alienation/difference is where the magic of cinema sleeps. Watching distant memories come to life with eerie ghost-like qualities, following shadows of people past, captured in a moment, immortalised through the longevity and magic of moving pictures.

Watching a film like Earth, you have to consider its context. It is impossible to place ourselves within its milieu but it does help to be objective about its subject matter of collectivism. It is in our ignorance that we pass this 78-minute film off as 'just a piece of propaganda'. Like The Birth of a Nation 15-years previously, its politics reflect time, place and the subjectivity of its director. The old adage, 'you have to look at it in a historical context' does ring true but this is silly and impossible (unless you can build a time machine). It is however, possible (even in today's world) to enjoy and appreciate humanity (regardless of your age, creed or culture). Earth explores human truth, the universal cycle of birth, growth and death, which gives its story a beautiful and poetic practicality that transcends time. The plights of the worthless worker echoes throughout the frame, as does the anger, despair and fear of death.

Verdict: In an age of silent cinema, Dovzhenko explains universal human truths not through dialogue but through imagery and sound. The classical violin score sheiks and scratches with pain, reflecting the plight of the worker while the montage-like editing displays the horror of machinery. It is raw, disorientating and kaleidoscopic - it attacks us. Earth is a necessary purchase for anyone who is interested in the history, beauty and emotion of cinema. With a price tag of £6.99 (from a certain DVD supplier) you can't say no.

If you are interesting in reading more about Earth check out this fascinating article:-

http://uwf.edu/ruzwyshyn/dovzhenko/Earth.htm

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!