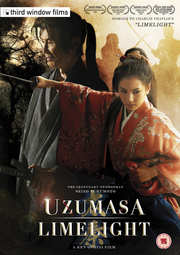

Review for Uzumasa Limelight

Introduction

This will be Third Window Films’ first ‘new’ feature film release in 2016, which given that it’s now April might make you wonder as to what’s going on. The first three months were devoted to debuting some well known Takeshi Kitano films on Blu-ray, and in previous years, Third Window Films have devoted time to restoring and releasing the Shinya Tsukamoto back-catalogue in high definition. There will be more Takeshi Kitano Blu-rays to come later on in the year, but the attention to back catalogue releases might give rise to some worrying conjecture. Actually it’s more than conjecture, as Third Window Films’ Adam Torel has spoken in interviews about the lamentable state of mainstream Japanese cinema. It’s going the same way as mainstream Hollywood, run by production committees, risk-averse, looking to the bottom line, and investing in ‘sure things’ such as sequels, and manga adaptations. The independent cinema that used to thrive on such situations is being squeezed out, starved of even the small investment that it needs to survive. It’s gotten to the point that Third Window Films has moved into film production, in order to procure the kind of films that are their bread and butter, the unique, the quirky, the challenging. Their first new film of 2016, Uzumasa Limelight manages to encapsulate the decline of a once vibrant and imaginative industry in its story, although it is in turn strongly inspired by Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight.

Kyoto’s film industry was built on the Samurai drama, and the unsung heroes of the industry were the Kirareyaku, those bit-part players whose job it was to die dramatically at the hands and blades of the films’ heroes. There used to be hundreds, but in an age where the samurai dramas are falling out of vogue, there is only a handful left. Seiichi Kamiyama is a veteran of the art, regularly dying on screen, and a fixture of the studio’s Edo Zakura series. But with a new, young executive at the helm of the studio, the old ways are on the way out, with fresh and new talent incoming. The forty year old television series is unceremoniously cancelled, and it looks as if Kamiyama’s career is on the decline. A confrontation with a director sees him taken off screen, and he’s left to perform in a studio attraction for visitors and tourists.

A new wannabe actress named Satsuki Iga joins the studio, and she’s fascinated by the sword skills of the talented performers. When a new samurai drama is announced by the studio, Kamiyama may still be persona non grata with the director, but he finds that he can still impart his knowledge and experience to Satsuki, and that is enough to get her noticed.

I’m reviewing the DVD edition of the film, but it’s also released on Blu-ray on the same day.

Picture

Uzumasa Limelight gets a 1.85:1 anamorphic NTSC transfer, which is encoded progressively on this disc for 24fps playback on compatible equipment. It’s a recent film, shot digitally as so many are, so the transfer is free of any problems, clear and sharp throughout with consistent colours. Given the subject matter though, the framing and choreography of the action sequences, and the wonderfully evocative cinematography, I do wish that this had been shot on actual film. There are moments in the movie that really stand out in terms of visual impact, a training sequence silhouetted against a setting sun, or the opening action sequence, also in silhouette, that really speak to the cinematographer’s craft. But then again in more mundane, quieter scenes, you can see the lack of contrast due to the digital medium, a fall off in dark detail that is a little disappointing.

Sound

The sole audio track on this disc is a DD 5.1 Surround Japanese track, with optional English subtitles. The dialogue is clear throughout, and the surround track is effective for the film’s action sequences, establishing ambience, and immersing the viewer in the film. The music soundtrack is certainly evocative, and works well to carry the story. The subtitles are timed accurately, and are free of typographical error.

Extras

Uzumasa Limelight is presented on this disc with an animated menu. In the extras you’ll find the film’s trailer (2:03), and a Behind the Scenes featurette (22:50), comprising b-roll footage interspersed with a few interviews.

Conclusion

When I first heard of Uzumasa Limelight, I was put in mind of Millennium Actress, the Satoshi Kon animated feature that celebrated the Japanese film industry in a typically mind-bending and emotionally evocative way. Millennium Actress would be a hard act to follow, if Uzumasa Limelight offered something similar. Uzumasa Limelight isn’t like that at all though, and if it does celebrate Japanese cinema, it does it in a wry and cynical way. It recognises the decline of a creative industry overtaken by crass commercialism, failing to respect what has come before and honour those who had built it in the first place. It does of course celebrate the past, the history of the Samurai film genre, and the actors like Seiichi Kamiyama who were its mainstays. Kamiyama is played by Seizo Fukumoto, who himself has had a long career as a kirareyaku, dying tens of thousands of times on screen.

Uzumasa Limelight is inspired by Chaplin’s Limelight, but it also put me in mind of a whole class of films that I have enjoyed watching, films like Tough Guys, and The Shootist, where aging protagonists live past their prime, entering a new, unrecognisable age where their talents are outdated, the world passes them by, and they have a hard time coming to terms with their lot, only for fate to offer them one final chance at fame. The Shootist is perhaps the most apt comparison, it was John Wayne’s final film, playing an aging gunman at the start of the twentieth century, with law and order having caught up to his world, facing a slow death through illness, or one final blaze of glory. Made in the seventies, it was also one of the last of the Hollywood Westerns, not as grand or as colourful as those of the genre’s heyday, and a sign that the age of Cowboys and Indians was on its way out. Of course ten years later Hollywood would be making Young Guns. The forties and fifties were big on swashbuckling epics, Errol Flynn and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. films with plenty of swordplay. They all went away for a while, and then a certain George Lucas made Star Wars...

Uzumasa Limelight isn’t about the death of a genre, indeed its story might show the end of one Samurai show that seems to put paid to Kamiyama’s career, but it also shows the start of another, made in the crass commercial reality of the new world, with truncated green sticks standing in for swords (to be filled in with CGI), and a pop-star lead actor who refuses point blank to have the traditional chonmage haircut for fear of alienating his fans. This film, once again mirroring a Hollywood reality, is about the death of the studio system, which this film suggests has lasted longer in Japan than it did in the US.

When the film begins, we’re seeing the death throes of the studio system, a world that has essentially become a family, with actors living close to, or on the studio set, forming close relationships. The working day begins with a casting board, with the contract players’ names etched into tags, put against the roles as extras they will be playing that day, in the various productions being shot at the studio. It’s all one, close-knit family, but a family that looks set to be torn apart when the harsh realities of the modern world impact. The new studio exec is driven by commercialism, not tradition, so the first thing that goes is the 40-year old Samurai Drama, it’s cast and crew only told on the last day of filming. With no other such shows in production, that leaves Kamiyama out in the cold. A sole attempt as an extra on a modern detective drama is scuppered by a new director who cares little for the welfare of his supporting cast.

The decline seems inevitable, with Kamiyama sidelined to a role in a studio attraction, performing for visitors and tourists, and with age inevitably encroaching. But it’s the arrival of up and coming star Satsuki Iga that offers some prospect of reprieve, indirectly at least. When she first joins the studio, it’s also as a bit player, trying to get roles as an extra. But she loves the Samurai dramas, and has an appreciation for the art of theatrical swordplay. Reluctantly at first, Kamiyama takes her under his wing, and a mentor student relationship develops. As Satsuki becomes more proficient, she gets noticed by the executives, and actually gets a role in a show. But it’s as her personal career develops, that in contrast the studio’s fortunes decline. It’s not so much the imparting of skills, as it is the imbuing of the work ethic, the sense of family that comes with the old studio system that sticks with Satsuki, and it’s this that eventually offers Kamiyama his long overdue time in the limelight.

And in a case of life imitating art, Uzumasa Limelight turned Seizo Fukumoto from the oft-slain kirareyaku into an award winning lead actor. Uzumasa Limelight is a gentle and heart-warming film, albeit with a slightly cynical, if not unjustified view of the Japanese entertainment industry, which like so many is now driven by commercialism rather than creativity. But it’s a reminder that while suits and money currently hold sway over the film industries all over the world, genres never really go away, and if you put in the work as well as the talent, rewards and accolades will eventually come to pass.

Your Opinions and Comments

Be the first to post a comment!